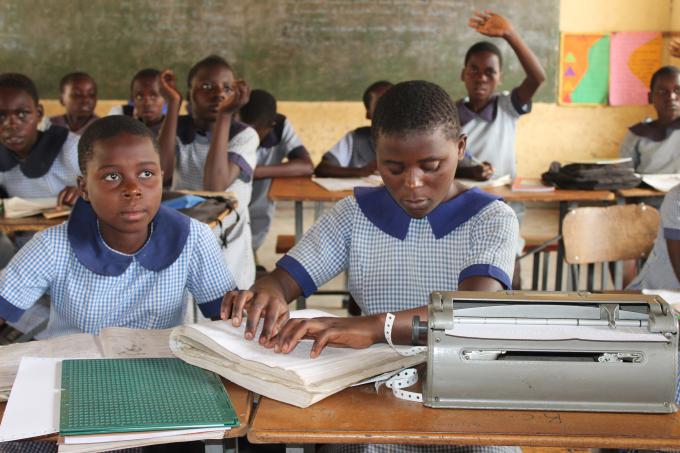

Visually impaired child defies all odds

Twelve-year old Ennert of Mahuwe Primary school is visually impaired but has been a shining star both at the resource unit for visually impaired children and the mainstream class at the school.

Ennert’s teacher Julian Zingwena says Ennert is well versed with her class lessons and continues to take the first position among the grade 5 stream.

Mahuwe school is situated in the outlying rural remote parts of Mbire District within Mashonaland Central province about 270 kilometres east of the capital Harare. It is here where Ennert is a beacon of hope and a rising star undergoing both braille lessons and mainstream lessons outshining over 235 classmates.

Ennert has excelled in all subjects using braille, at the resource unit for visually impaired children under teacher Zingwena’s class. She is among six visually impaired girls and five boys benefitting from Save the Children’s Inclusive education initiative, that provides braille stationery, spectacles, walking sticks, sound calculators among other materials at the school.

Zingwena reveals that Ennert joined the school for children living with visual impairments last year at the age of twelve and has never looked back.

‘Since Ennert came to attend Grade Four she has never disappointed during lessons. Besides her visual impairment she is naturally talented,’ explains Zingwena.

Her grade five mainstream teacher Doesmatter Marota is confident that Ennert will score five units in the Grade Seven public exams.

‘Ennert will pass in Grade Seven because she is committed despite her condition. She is gifted. She is doing well in English, Shona, Mathematics and General Paper. She is inspirational to us all as a school and as a community,’ says Marota.

Save the Children’s inclusive education initiative covers eight districts of Zimbabwe including Mbire, Rushinga, Matobo, Beitbridge, Binga, Hwange, Gokwe North and Gokwe South. It is implemented in partnership with the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education and Leonard Cheshire Disability Zimbabwe (LCDZ).

Martin James, LCDZ programs manager says they have worked with communities through community sensitisation and mobilisations that have helped children with disabilities to be enrolled in mainstream schools and attend lessons. In addition, LCDZ conducts workshops for all teachers at schools where a child who is hard of hearing has been enrolled after assessing children with disabilities professionally.

‘The children with mental, language and speech challenges or learning disabilities are assessed by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education’s Schools Psychological Services department while those with physical challenges are taken care of by Rehab Technicians under the Ministry of Health and Child Care,” explains Martin.

“Through Save the Children support, LCDZ facilitates the assessments of children with visual and hearing impairments by professional audiologists or ophthalmologists who are usually based in cities and also acquires assistive devices for children who may require them after assessments. We are happy that we are assisting disadvantaged members of the community and its paying off,’ says Martin.

The assistive devices are delivered to the children’s schools or homes. The project also offers counselling services to children with disabilities and their families. Some teachers often complain that they find it difficult to communicate with children with disabilities especially those that have hearing impairments.

Save the Children’s Education programme officer in Mbire district Beatrice Gambiza says Ennert is part of the success story for visually impaired children.

‘Mahuwe primary school is an informal boarding school for visually impaired children that was established after we conducted massive awareness campaigns on the importance of inclusive education. It is no longer catering for locals only. We have other children coming from as far as Guruve and Shamva districts,” says Gambiza.

‘The government no longer pays grants to schools for children with disabilities and it is affecting their welfare. This comes against a background where our country has very few specialist schools for children living with disabilities, and most rural areas have no such schools. We hope the government will consider reviving educational grants for children with disabilities,’ added Gambiza.

Mahuwe Primary School headmaster David Mujota admits that they are facing financial challenges to support children with disabilities, as few parents or guardians pay school fees and levies. ‘This is a challenge but we cannot forsake these children because no-one is paying fees,’ says Mukota.

The awareness campaigns in communities impacted positively on the importance of enrolling children with disabilities in mainstream schools across the eight districts. Save the Children has also availed materials for the school infrastructure adaptations, including construction of access ramps and pathways, making doors wider for easy access by wheelchair users and construction of toilets that are disability friendly with toilet seats and supporting rails.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe